BACK TO TOP

Step into the Vibrant Universe of Bengal’s Kalighat Paintings at Swadesh

Immerse yourself in fascinating stories of the paintings that went from being religious art to vivid documents of 19th-century BengalBy Sohini Das Gupta | 1st Apr 2025

Every time a new exhibit opens at one of Swadesh’s ever-evolving pavilions, it becomes a portal to the history of rare and exquisite crafts from diverse parts of India. While the pavilions themselves are built to invoke the romance of the regions, it is the sight of master artisans engrossed in their craft – painting, weaving, welding and carving away with generational finesse – that makes the cultural experience one-of-a-kind. Designed to celebrate the incredible talent of Indian artisans and our country’s centuries-old heritage, Swadesh has showcased over 30 artforms since its inception, including Pichwai painting, Blue Pottery, Sozni embroidery and Kal Baffi carpets, Thangka paintings, Dhokra art, Banarasi, Baluchari, Kanjivaram and Kalamkari Weaves, and many more.

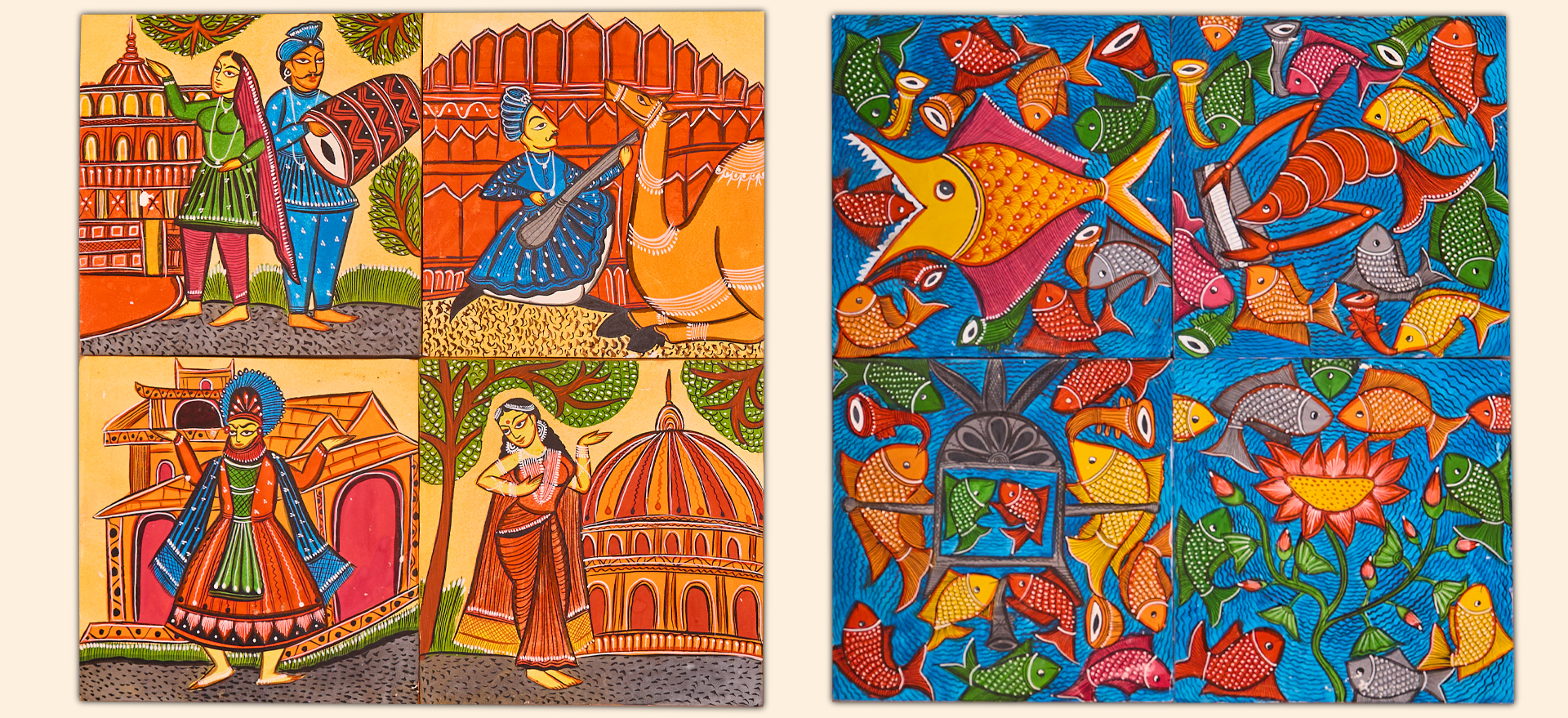

Among the pavilion’s current exhibits are Kalighat paintings and Bengal Patachitra – artforms with fascinating tales of an intertwined history and equally stunning details of strokes and colours. What makes these artforms even more compelling is the range of themes that they depict. True to Kalighat’s origins as a devotional form of painting, there are many scenes from Hindu mythology, but these are interspersed with scenes from daily life–a pedestrian by a car, a couple in embrace, a woman and her cat, a cat dreaming of flying fish. Whether the characters are traditional or contemporary, human or animal, they all carry the same bold flourishes and vibrant details, and often, a dazzling hint of satire.

The Kalighat painting style is an example of a genre that emerged out of sheer economic necessity. It originated in 19th century Bengal, during a time of great transformation. Calcutta, now Kolkata, had become a bustling port under colonial rule, and people from all parts of the country thronged the city looking for work. Some of these folks were artists, known as chitrakars, trained in the intricate tradition of patachitra or patua – a form of devotional painting typically practised on 20 feet-long scrolls. Calcutta was the ideal market for their work, bustling with pilgrims who were drawn to the Kalighat, a Kali Temple in the city. There, the chitrakars were surprised to find a customer base beyond the residents of this burgeoning city – European settlers who regularly bought art as souvenirs.

Facing greater demand than they had bargained for, the artists needed to work quickly. And so patachitra artists who had spent decades honing long narratives and intricate backgrounds slowly abandoned the laborious details, focusing instead on figures, outlines, strong colours, and the vivid eyes of their characters. The new style that emerged came to be known as the Kalighat style of painting – one that took the traditions of patua and reimagined them with bold outlines and bright hues. Steadily, these paintings started to depict more than just religious figures and their legends, as scenes from daily life became the new focus. Kalighat paintings acquired a knack for capturing social oddities, idiosyncrasies and hypocrisies–including the rise of ‘babu culture’, or the shenanigans of hedonistic aristocratic gentlemen. They were also progressive in their gaze, depicting women as equal to male counterparts. Over time, the universe of Kalighat paintings became a vibrant document of life in 19th and 20th century Bengal, a touchstone in Bengal art even today. As machine production made souvenir art cheaper and easier to produce with the passing of the years, the Kalighat masters could no longer compete, and the art started to disappear from mainstream popularity. Luckily for the world, the chitrakars of Midnapore and Birbhum in West Bengal have worked hard over the decades to preserve the craft, passing down their fine strokes across generations.

Step into the Kalighat Painting pavilion at Swadesh, and the calendar turns back two centuries. By shining the spotlight on a lost time, and an all-but-lost tradition, Swadesh ensures that Kalighat paintings continue to attract the attention of audiences and artists alike – two pillars instrumental to carrying the artform into the future.